Income taxes are complicated enough with a couple full-time jobs, some children, and a mortgage without investments adding a whole new layer of complexity. The good news is that taxes on investment income is rather straightforward with the exception of a few important caveats. As investment income grows over time, it’s important to understand these tax caveats to minimize taxes and maximize retirement income.

In this article, we will look at nine frequently asked questions about investment income taxes and identify some of the important caveats.

Do I owe taxes when selling stocks or bonds?

Not necessarily.

The amount of tax owed when selling an investment depends on the cost basis, the holding period, and your tax bracket.

Investors don’t owe any tax on investments that are sold for a loss – that is, when the sale price is lower than the cost basis. In fact, investors can use this loss to offset other capital gains or income taxes. Some investors will intentionally realize a loss to offset other capital gains taxes in a strategy known as tax-loss harvesting (see below for more details).

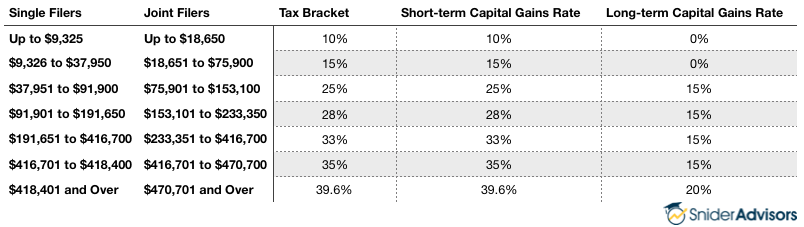

Investors selling a stock or bond for a profit must pay taxes on the difference between the cost basis and the sale price. Investments held for longer than a year qualify for long-term capital gains tax rates, while those held for less than a year are subject to short-term capital gains – or ordinary income – tax rates. The exact tax rate is subject to change each year and depends on your specific tax situation (see Figure 1 below for 2017’s tax rates).

Figure 1 – 2017 Investment Income Tax Guide

There are also some other unique situations where tax rates may differ from these norms, such as inherited stocks or so-called “return of capital” payments. Investors should consult a tax professional in these situations to determine the exact amount of tax owed.

Long-term and short-term capital gains are reported on Form 1040 Schedule D.

How are dividends taxed?

Dividends are regular payments made by a corporation to their shareholders as a distribution of profits. While there are many different types of dividends, the most common dividends are paid quarterly by large blue-chip stocks.

The amount of tax paid on dividend income depends on whether they are qualified or ordinary dividends. These classifications are made based on the length of time that the underlying stock has been held and the tax owed depends on the investor’s tax bracket.

- Qualified dividends are payments made by stocks that an investor has held for more than 60 days during a 121-day period that begins 60 days before the ex-dividend date. Preferred stocks must be held for 90 days or more during a 181-day period that begins 90 days before the ex-dividend date for dividends to be qualified. These dividends are taxed at the long-term capital gains rate.

- Ordinary or non-qualified dividends are payments made by stocks that don’t fit these criteria and are taxed at the ordinary income rate.

Qualified and unqualified dividends are both reported on Form 1099-DIV and must be disclosed on Form 1040. Investors earning more than $1,500 in ordinary dividends may also need to file Form 1040 Schedule B to provide specific details.

How is interest income taxed?

Interest income comes from many different sources, ranging from interest-bearing bank accounts to bond payments. This income is subject to the ordinary income tax rate with the exception of U.S. Treasury bonds, savings bonds, and certain municipal bonds.

Interest income is reported on Form 1099-INT by banks and other financial institutions and taxpayers must disclose interest on Form 1040 Schedule B.

Are muni bonds really tax-free?

Yes and no.

The interest income generated by municipal bonds is typically exempt from federal income tax with a few exceptions. In addition, investors buying muni bonds in their home state may also qualify for a break on state or local income taxes.

The catch is that muni bond income must be included when calculating modified adjusted gross income – or MAGI – in certain situations. This means that muni bond income can impact how much someone pays in Medicare Part B monthly premiums or Social Security taxes.

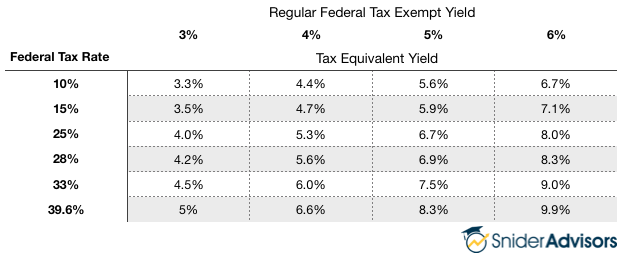

The upshot is that muni bonds still make a lot of financial sense for many investors, particularly those that fall into a high tax bracket (see Figure 2 below for tax equivalent yield examples).

Figure 2 – Tax Equivalent Yield Guide

Investors should consult with an investment and/or tax professional before purchasing municipal bonds given their somewhat complex nature.

How are options and other derivatives taxed?

The short answer is: It depends.

The tax consequences of options depend on the type of option, whether it has been exercised, whether it’s covered or uncovered, whether it’s short or long, and other factors.

The general tax implications include:

- Exercised long options result in capital gains or losses.

- Expired long options result in a capital loss of the premium.

- Exercised short options result in a capital gain or loss.

- Expired short options result in a capital gain of the premium.

Investors should consult with a tax professional to determine their specific tax exposure when it comes to the use of options and other derivatives given their complex nature.

How are international investments taxed?

You must pay tax on foreign investment income, but you might get it back in the form of a tax credit.

Investors must report all foreign investment income on Form 1040 in U.S. dollars, even if they are already paying foreign taxes on the investments. The upshot is that investors may file Form 1116 to receive a foreign tax credit to avoid double taxation. Investors who paid less than $300 in creditable foreign taxes can also usually deduct the taxes paid on Line 51 of Form 1040.

Offshore funds and other investments are significantly more complex when it comes to paying taxes, which means that investors may want to consult an investment and/or tax professional in those situations to maximize their tax efficiency.

How are REITs and MLPs taxed?

Real estate investment trusts – or REITs, master limited partnerships – or MLPs, and other corporate structures may have different tax implications than traditional stocks and bonds.

Most REIT dividends are taxed as ordinary income, but there are some exceptions when the REIT makes capital gains distributions or a return of capital distribution. By contrast, MLP income is typically taxed at short- or long-term capital gains rates, but the income, losses, and dividends are reported on a Schedule K-1 and sent to the IRS with a Form 1065. Unfortunately, these additional documents are more complex and will require extra work by a tax preparer.

Investors should consult a tax professional in these cases in order to avoid any costly mistakes.

What is tax loss harvesting?

Tax-loss harvesting is a strategy that involves selling a security that has experienced a loss. By realizing the loss, investors can offset taxes on other investment gains and/or income. The security that was sold is replaced with a similar one, which maintains an optimal asset allocation and expected returns.

The catch is that you can’t buy a “substantially identical” security within 30 days before or after the sale of the original security. The so-called wash sale rule disqualifies the loss and the cost basis is added to the remaining shares. In general, investors should try and purchase a replacement security that has similar exposure, but is sufficiently different.

What is the Net Investment Income Tax?

The net investment income tax – or NIIT – is an extra 3.8% tax on net investment income for high net worth individuals. The tax was originally passed as part of President Obama’s Affordable Care Act in 2013, but may be repealed by the Trump Administration.

Individual filers with an aggregate gross income of more than $200,000 or joint filers with an AGI of more than $250,000 must pay tax on investment income that exceeds those thresholds. For example, a single filer that has a salary income of $150,000 and net investment income of $60,000 must pay tax on the $10,000 that exceeds the $200,000 threshold.

The Bottom Line

Investment income taxes are generally straightforward with sales generating short- and long-term capital gains and interest income generating ordinary income taxes. Of course, there are some situations where these rules may not apply and other cases where investors can take advantage of tax strategies to maximize income.

This material has been prepared for informational purposes only. Snider Advisors is not a tax advisor. Always consult a tax professional regarding your specific situation.